Frühbeck Brings Mahler's Epic Vividly to Life

There are times when words fail. That’s why there is music.

Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra demonstrated this axiom to the fullest with Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 Thursday evening (Oct. 4) at Music Hall.

Frühbeck, who is entering his second season as creative director of the CSO, led an eloquent and deeply felt performance, earning a unanimous ovation as the last musical syllable rang through the hall. Conducting for nearly 100 minutes straight (there was no intermission and he conducted seated), Frühbeck kept the CSO totally absorbed, channeling Mahler’s vision with precise and telling gestures. Despite its length – Mahler’s Third is his longest symphony and one of the longest ever written -- the audience remained rapt throughout (it can be a challenge for those with short attention spans).

Mahler’s vision is of the world, a kind of musical “Origin of Species,” proceeding from the emergence of life from inanimate matter, to the highest manifestation of being, universal love. He assigned descriptive titles to its six movements, though he later omitted them to avoid being too literal.

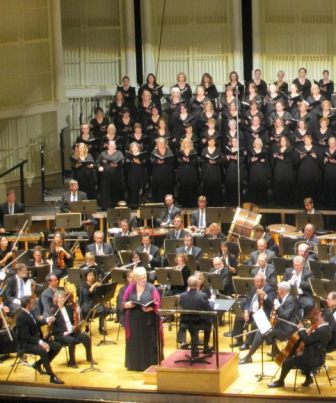

Carrying out this task requires scores of musicians. Onstage for Thursday’s performance were the CSO, enlarged to 103 players, mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe, 100 women of the May Festival Chorus, directed by Robert Porco, and 55 members of the Cincinnati Boychoir, directed by Christopher Eanes. Fortunately, Music Hall was built for such things, and it accommodated them easily, both logistically and acoustically.

Interestingly, Mahler's Third Symphony was given its U.S. premiere at Music Hall -- by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra led by music director Ernst Kunwald at the 1914 Cincinnati May Festival.

The colossal first movement, “Pan Awakens, Summer Marches In,” opened with a powerful statement by the French horns (all eight in unison). One-third the length of the entire Symphony, the movement is permeated with marches, flourishes, trumpet calls and a melee of life stirring and asserting itself. The brasses (18 in all), who must act as a kind of band-within-an-orchestra, performed with snap and skill, joined by a corps of expert percussion (augmented to five players, plus timpanists Patrick Schleker and Richard Jensen). Principal trombonist Cristian Ganicenco’s burnished solos provided reflective commentary throughout.

The second movement, “What the Flowers in the Meadow Tell Me” (one of Mahler’s most popular excerpts), opened with a gentle oboe solo and a soft wash of strings, evoking the waltz-like Austrian ländler. For the third movement, “What the Animals in the Forest Tell Me,” Mahler appropriated a song he wrote on a poem from “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” (“The Youth’s Magic Horn”) about a cuckoo yielding the stage to a nightingale. The animals’ antics get interrupted, however, by an offstage posthorn, signaling man’s arrival on the scene. It was a transfixing moment, with CSO principal trumpeter Robert Sullivan, performing backstage on an authentic antique posthorn. Frühbeck gave perfect continuity to this complex movement, with its halting moments and cautionary implications. (Mahler intimates that all may not be well with the ascent of man, and there is a brief, but chilling reference to the Judgment Day music from his Second Symphony near the end.)

The fourth movement, “What the Night Tells Me,” utilizes “The Midnight Song” from Nietzsche’s “Also sprach Zarathustra.” Blythe was an affecting soloist in this philosophical departure (“O man, give heed”), which impressed itself deeply throughout the hall. Literally and figuratively “tief” (“deep”), with predominantly dark instrumental colors, it also featured exquisite solos by concertmaster Timothy Lees.

“What the Morning Bells Tell Me” followed without a break, with the Boychoir sounding the bells with their voices (“bimm, bamm”). It was a truly angelic movement, again incorporating one of Mahler “Wunderhorn” songs, “Es sungen drei Engel,” (“Three Angels Were Singing”), rendered beautifully by Blythe and the May Festival choristers. Frühbeck led with particular intensity and engagement here, rarely glancing at his score, then moving ever so smoothly into the finale, “What Love Tells Me.”

This great Adagio, a departure from the usual fast-paced finale, is the apotheosis of the work. It brims with melody (did Sammy Fain cop “I’ll Be Seeing You” from this movement?) and had many in the audience visibly moved. As Frühbeck built to its heart-swelling conclusion, he stood, and with sweeping gestures, seemed to embrace the entire ensemble with his arms. There was an immediate response from the crowd, which rose as one in a hail of bravos and applause. As Frühbeck, Blythe, Porco and Eanes took their bows, the orchestra and choruses showered them with their own applause.

The concert, a must for Mahler fans and those who may wish to get to know him at his most colorful, repeats at 8 p.m. tonight at Music Hall. Tickets, beginning at $10, are available at (513 381-3300, online at www.cincinnatisymphony.org and at the Music Hall box office before the performance.