Mozart to Stravinsky: CSO, Hahn Shine

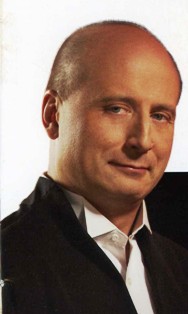

This weekend’s

Cincinnati Symphony concert at Music Hall (Dec. 17 and 18) had “special”

written all over it.

It marked

the return of music director Paavo Järvi to the podium after a three-month

absence, a guest appearance by one of today’s certified stars, violinist Hilary

Hahn, and a delectable program of chamber-sized repertoire.

Indeed, the Cincinnati Symphony became a chamber orchestra, a welcome guise that demonstrated the flexibility of the orchestra, as well as the extraordinary talent that dwells within it. With members of the CSO playing concurrently for Cincinnati Ballet’s “Nutcracker” at the Aronoff Center, it was an illustration of the value of a fine orchestra and the multiplicity of ways in which it can serve a community.

Multi-Grammy winner Hahn, one of the finest violinists before the public today, performed Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 5 in A Major -- called the “Turkish” for its colorful Turkish-flavored episode in the final movement. With a complement of 25 strings plus pairs of horns and oboes, ensemble was perfect, a word that also begs to describe Hahn's exquisite playing.

The balance of the program was three works for chamber orchestra, Bartok’s 1939 Divertimento for strings, Benjamin Britten’s “Simple Symphony” and the Suite from Stravinsky’s music for the ballet “Pulcinella.” All were performed completely in front of the stage's double proscenium arch, with the acoustical towers aligned horizontally behind them for a “close-up,” intimate experience (at least to the extent the huge hall allows).

Winsome in a long, sea-blue gown, Hahn, 31, was every inch a star. But her true greatness lay in her consummate musicality. Allied with Järvi and the CSO, she presented a classically refined performance, full of detail and nuance, always at the service of the composer. If one may fumble for a metaphor, the music was the aural equivalent of a piece of finely-painted, classic sculpture.

Hahn played with a bright, smooth tone, utilizing tight bowing and tasteful vibrato. Interaction with the CSO was pinpoint precise, and the winds added a layer of great beauty, as in the outer movements where her sound blended with principal oboist Dwight Parry's in some ravishing, jewel-like moments.

Her cadenzas exhibited grace as well as virtuosity. They were like small essays, spun with grace, polish and in the second movement, supple double stopping. She, Järvi and the CSO put lots of zing into the Turkish episode in the finale where the cellos and double basses relished playing rhythmic accents with the wood of their bows.

Responding

to the crowd’s ovation, Hahn performed encores by Bach, the Sarabande (Friday)

and Bouree (Saturday) from his Partita in B Minor for violin solo. (For Saturday’s audience, she donned a Santa

Claus cap before returning to the stage for her encore.)

Järvi opened the concert with Bartok’s Divertimento, a work written on the cusp of World War II during a special moment carved out for him by conductor/patron Paul Sacher at a retreat in the Swiss Alps. In three movements, it is modeled on the baroque “concerto grosso,” i.e. with a solo quartet playing against a larger ensemble. Hungarian folk flavor abounds, particularly in the outer movements. The central Adagio, however, was filled with pain, even horror, as ominous trills and hammer blows intruded on the stillness of the music (premonitions of the conflagration to come are read into this).

CSO principal players excelled in the demanding work, which, particularly in the Allegro finale, is filled with rapid exchanges. Järvi played his hand beautifully at the end, which alternates pizzicato with rushing figures, leading to a fortissimo conclusion.

Britten’s “Simple Symphony” belies its title, for, like Bartok’s Divertimento, more resides in it than would be apparent from such a designation. It is short, often sweet and perky – the pizzicato second movement was a delight – but the slow movement, “Sentimental Saraband,” ached with something more. Often heard separately, the music is heart-rendingly beautiful, suggesting the composer’s deep feelings of nostalgia (the work is built on compositions he wrote as a child). Järvi led it heart-on-sleeve with great tenderness. By contrast, he brought out all the prankishness and good humor of the other three, with plenty of boisterousness in “Boisterous Bouree” (when does it end, really?), playfulness in “Playful Pizzicato” (is that a big guitar or what?) and frolic in “Frolicsome Finale” (with some conductorial choreography to boot).

Stravinsky’s “Pulcinella” Suite called upon the individual and corporate virtuosity of the CSO. The work is drawn from his music for Serge Diaghilev’s 1920 ballet “Pulcinella” based on the Neapolitan commedia dell’arte, with Pulcinella (also known as Punch) tormenting ladies and gentlemen alike with his amorous mischief. It is a brilliant and challenging score (audition material for many an instrumentalist) and called for playing to match. Like Bartok’s Divertimento, it is written in concerto grosso style and was the first of Stravinsky's great neo-classic works.

Less was more here, with an orchestra of 42, including a “concertino” of five strings (two violins, viola, cello and double bass). It was a glory day for the CSO winds, as well, all of whom had moments to shine: Parry in the lovely Serenata; principal flutist Randolph Bowman in the Gavotta; and principal bassoonist William Winstead, also in the Gavotta (second variation), where he was joined in a taxing sixteenth-note accompaniment by bassoonist Hugh Michie. Trombonist Cristian Ganicenco had some of the best lines of the evening in the comical Vivo, where he was joined in some delightful solos by principal bassist Owen Lee. As for concertmaster Timothy Lees and the other CSO principals -- violist Christian Colbert, cellist Ilya Finkelshtyn and violinist Kun Dong filling in for Gabriel Pegis -- they shone everywhere.

No one seemed to have more fun than Järvi, who

brought the Finale of the Suite to an end with an airy tune, begun in the flute,

which gave way to raucous rhythmic repetitions and an emphatic sign off.