Hearing -- and Seeing -- Music

(first published in the Cincinnati Enquirer June 7, 2010)

You might call it "Tin Pan Alley meets the Emancipation of Dissonance,"

and they were not such an odd couple after all.

In one of the more original programs of the season, Mischa Santora and the Cincinnati Chamber Orchestra paired George Gershwin and Arnold Schoenberg Sunday afternoon in Corbett Auditorium at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music.

Santora brought them together through the medium of painting. Both composers painted on the side. They met and became friends in Los Angeles during the 1930s and 40s. They were tennis partners and even painted each other. The concert was a multi-media event, with images of their paintings and others projected onto a screen beside the orchestra during the performance

Few of Gershwin's paintings are actually accessible to the public,

said Santora, but pianist Michael Chertock filled that gap handily in

renditions of Gershwin's "Rhapsody in Blue," Three Preludes and "Grand

Fantasy on Airs from 'Porgy and Bess' " (Earl Wild), that were splashed

with all the color and gesture one could wish.

Schoenberg may not

lend himself as easily as Gershwin to displays of digestible color, but

as he hoped during his lifetime, listeners' ears have caught up with him

to some extent. This certainly holds true for his 1899 "Verklärte

Nacht" ("Transfigured Night"), a kind of last gasp of late romanticism

based on a poem (by Richard Dehmel) about lovers reconciling in the

moonlight after she confesses to being pregnant by another man. As

performed by Amy Kiradjieff, Cheryl Benedict (violins), Heidi Yenney,

Wendy VanderMolen (violas), Patrick Binford and Tom Guth (cellos), it

was agitated, impassioned, ethereal and tonal, abundantly laced with

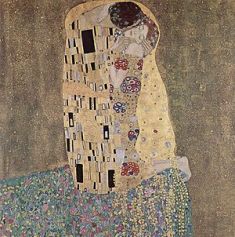

chromaticism. Paintings by expressionist master Gustav Klimt ("The

Kiss," etc.) enhanced the aural megawattage.

Chertock is without

doubt a master of Gershwin. His Three Preludes were like second nature,

bright, brilliant and bluesy, and he ended Wild's rhapsodic

transcription with a gorgeous, singing "Bess, You is My Woman Now."

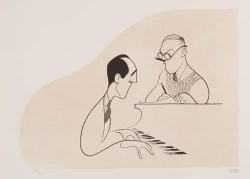

Gershwin the painter was demonstrated by Santora in remarks preceding

Chertock's performance with a projection (photo) of Gershwin painting Schoenberg

and Gershwin's painting,"Man in a Top Hat," of Gershwin painting himself.

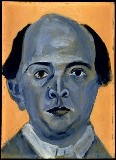

The Schoenberg show continued in earnest after intermission with his Five Pieces for Orchestra in its 1925 version for chamber orchestra. The composer had truly "freed dissonance" here, but had not yet adopted the "12-tone" formal system which revolutionized 20th-century music. The five movements have programmatic titles, but they were only added to please Schoenberg's publisher, Santora said.

Hearing the CCO

perform this music to projections of Schoenberg's paintings and those by Expressionist Wassily Kandinsky (a great influence on

Schoenberg and vice versa) served as a reminder that our ears have

already been trained for such "difficult" music - at the movies, where there is a visual element to underpin the most challenging scores.

Nothing seemed the least bit unusual here, though seeing Schoenberg's

self portraits and Kandinsky's energetic canvases did help cement

impressions.

Santora led the CCO with great skill and perception. "Premonitions" was quiet and spooky, "The Past" slow, drifting and beautiful. The most famous movement, "Chord Colors," also known as "Summer Morning by a Lake," shimmered with sunlight and occasional "splashes" of fish. "Very fast" was spiky and swift. The final movement, a stylized waltz spoke for itself, without projections.

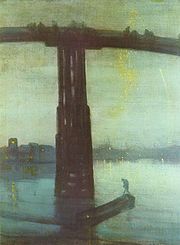

Why the title "Rhapsody in Blue" for Gershwin's most famous work?Why not?

Nocturne in Blue and Gold (Battersea Bridge) by James McNeill Whistler

|

CCO assistant conductor Kelly Kuo led in its 1924 jazz orchestra version. Chertock's performance was extremely vivid, from bright and steely to suave and romantic on the lush, "big" theme that ends the work. The CCO generated a kaleidoscope of color, from clarinetist John Kurokawa's opening "smear" (delicious) to Marc Wolfley's snappy snare drum. It all came together at the end in a big swagger than lifted the audience from their seats.