A Comeback for Cincinnati Opera's "Otello"

All’s well that ends well.

This tag would never fit Shakespeare’s “Othello, but it seemed just right for Cincinnati Opera’s production of Verdi’s “Otello” Saturday night at Music Hall.

Opening night, July 7 at Music Hall, had been star-crossed, with tenor Antonello Palombi in the title role suffering inflammatory tracheitis. (Opera artistic director Evans Mirageas made the announcement after act II, but Palombi soldiered on to the end.) After seeing a pair of otolaryngologists the next day and giving his voice a rest, Palombi came back, if not as good as new, well able to give Shakespeare’s Moor a satisfying performance.

With a fine cast behind him, an evocative production and Robert Spano leading the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, it made for a compelling evening.

It was not just Palombi who came back stronger. With his indisposition and one less performance to go on, opening night was somewhat edgy, and there were problems with balances, pacing and staging. The CSO sometimes overpowered the singers – at least from my vantage point on the orchestra level -- and the final act sagged. Desdemona’s “Willow Song” and “Ave Maria,” while plaintive and touching, moved too slowly, and her whispered refrain ("salce," “willow”) did not project well in the huge hall.

However, Saturday’s repeat triumphed over adversity and left the crowd cheering happily.

Closely based on Shakespeare with libretto by Arrigo Boito, “Otello” takes place in 15th-century Cyprus. Otello is a Moorish general in the Venetian army. His ensign Iago has been passed over for a promotion and is intent on revenge. He gets it by preying on the weaknesses of others. He plies his rival Cassio with drink and gets him dismissed by Otello, then persuades Cassio to ask Otello’s wife Desdemona to intercede for him. Iago suggests to Otello that Cassio and Desdemona are lovers. A disappearing handkerchief (courtesy of Iago) provides “proof” of her infidelity and Otello kills her.

Cincinnati native Tom Fox as Iago stole the show (as villains are wont to do). Last-minute replacement for ailing Carlo Guelfi, the tall, strapping baritone served as a potent reminder that Verdi originally entitled his opera “Iago.” Bald and garbed in black leather, he manipulated the action like an evil puppet master. The opening of act II provided a vivid stage picture, with Iago standing alone at the top of the stairs, silhouetted boldly against the sky and gazing fixedly at the audience.

One of the highlights of the opera was Iago’s act II “Credo” (“I believe in a cruel god”), a kind of satanic creed sung before a gigantic crucifix. As Fox breathed the final words, “E poi? La morte e il nulla” (“And then? Death is nothingness”), the light went out on the crucifix followed by demonic laughter. He was swaggering and jovial in the act I drinking song (“Roderigo, beviam”), where Iago sets his plot in motion by getting Cassio drunk, and he tormented Otello mercilessly in act II with his wheedling “description” of Cassio’s lustful dream about Desdemona.

Italian soprano Maria Luigia Borsi was the image of the hapless Desdemona, fetching in long blonde curls, with a radiant voice to match. She was completely convincing as Otello’s wronged wife, whether receiving floral tributes from children in act II – a charming scene with members of the Cincinnati Opera Chorus and the sounds of mandolin and guitar in the pit (Paul Patterson and Timothy Berens) – or dissolved in tears in act III, when Otello inexplicably throws her to the ground in front of a delegation from Venice. On Saturday, saintly in white, she delivered her “Willow Song” with just the right mix of intimacy and intensity.

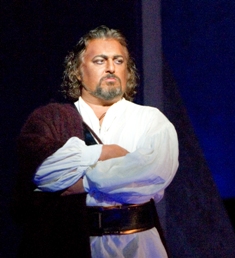

Palombi is without doubt one of today’s finest dramatic tenors. He made a complex, intensely human Otello, torn by love, jealousy and anger. His love scene with Borsi in act I, somewhat lacking in sparks opening night, was more ardent Saturday. The CSO cellos set the scene exquisitely, upper strings and harp introducing Borsi, as the lovers exchanged kisses by moonlight.

Palombi colors his voice with great skill. It was full of tenderness in the love scene, anger in his exchanges with Iago and Desdemona as he succumbs to jealousy over her supposed infidelity, and profound sorrow at the end, where, crumpled on the floor, he bid farewell to her corpse. A more heartrending goodbye has likely not been witnessed on the Music Hall stage since tenor Richard Leech as Romeo took leave of Juliet in Gounod’s “Romeo and Juliet” in 1989.

Supporting roles were well played by tenor Russell Thomas as Cassio (keep your eye on him); mezzo-soprano Catherine Keen as Desdemona’s maid Emilia; tenor Gregory Turay as Iago’s pawn Roderigo; bass Nathan Stark as Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus; and bass Denis Sedov as the Venetian ambassador Lodovico. The Chorus’ big moment was in act I, the dramatic storm scene where the Cypriots await the arrival of Otello’s ship and the lively, contrasting “Fuoco di gioia,” where the townspeople celebrate around a bonfire.

Spano and the CSO, a prodigious alliance both nights, did full justice to Verdi’s Technicolor score, beginning with the huge fortissimo discord that opens the storm scene. The brasses shone brightly during the arrival of the Venetian ambassador in act III, English hornist Christopher Philpotts added soul and depth to the “Willow Song” and the double basses joined in a rare extended solo in act IV where they accompanied Otello’s arrival in Desdemona’s bedroom in tones of dark velvet.

Visually, the production by Allen Charles Klein was simple, a raised platform with an opening in the middle and two staircases. Mosses hung from the ceiling, and the walls (Otello’s castle) appeared battered and worn. But what the Opera’s Thomas Hase did with the lighting! From real to surreal – from the dimly-lit storm scene to the ruby-red bonfire – it drew the viewer into the spell that only opera, with its marriage of aural and visual elements, can create. Red lighting was liberally used (blood, hellfire) and a huge, golden lion of Venice basked in bright light in act III. The warm-lit blues and whites of Desdemona’s bedroom had a Madonna-like aspect until splashed with red when Otello murdered her.

There were some disconnects between the

libretto and the stage action. Otello stabbed Desdemona instead of strangling her, as Iago had advised in

act III. And oddly enough, considering

what Otello states in the libretto -- and

was projected clearly in the surtitles -- i.e. “Ere I killed you, wife, I

kissed you,” he merely stood at her bedside and stared down at her before

killing her. By and large, the Chorus stood and sang most of the time, with little guidance on how to liven up the action.

Cincinnati Opera closes its 2010 60th-anniversary season with Puccini’s “La Boheme” July 21, 23 and 25 at Music Hall. For information and tickets, visit www.cincinnatiopera.org