Shostakovich, Tormis Aptly Paired on New CSO Disc

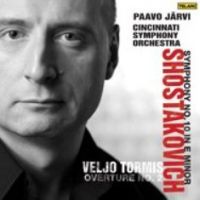

Paavo Järvi: Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Shostakovich, Symphony No. 10 in E Minor. Veljo Tormis, Overture No. 2. Telarc.

This is a blockbuster album, not only for Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony but for Estonian composer Veljo Tormis’ 1959 Overture No. 2.

Buyers will be attracted by the more familiar name – and certainly the Russian composer’s Symphony No. 10 is among the most powerful works of the 20th century.

But Tormis' unassuming-looking work is no filler. That becomes dramatically clear when you hear what Shostakovich’s younger, Estonian colleague wrote under similar circumstances, i.e. living in the Soviet Union during the Stalinist era.

CSO music director Paavo Järvi is a master of programming, as audiences in Cincinnati know (Mahler’s 9th Symphony and Messiaen’s “Ascension” on the same program, for example). Järvi is also Estonian and though he grew up well after Stalin’s terror, knows a thing or two about the Soviet system.

Shostakovich wrote his 10th symphony just after the Soviet dictator's death in 1953 and it, like all of his music, is drenched with meaning. The famous Allegro scherzo, a brutal four-minute portrait of Stalin, finds echoes in Tormis’ Overture, a potential symphony movement if Tormis had not devoted himself exclusively to choral music thereafter.

The pathos of Shostakovich’s 10th is also there, including a touching moment where the strings answer the trumpets with mournful strains right out of Sibelius’ “Valse Triste” (one of Järvi’s favorite encores).

Järvi’s reading of the Shostakovich is one of total integrity. It is true to the work’s musical aspects, including remarkable transparency and precision, as well as to the feelings expressed. The opening movement, almost as long as the other three combined, is filled with roiling emotions. Concertmaster Timothy Lees’ solo at the end, warmed gently with vibrato, touches the heart.

The Stalin juggernaut is overwhelming without being maniacal and shows off the virtuosity of all sections of the orchestra, from strings to percussion.

The Allegretto movement, the most personal of all, utilizes Shostakovich’s musical motto DSCH (“spelled” D, E-flat, C, B-natural in German notation). It recurs in a multiplicity of circumstances, a kind of metaphor for oppression. Principal hornist Elizabeth Freimuth soars on her repeated, arching solos.

Järvi found a comedic voice in the finale, devastatingly so near the end in a flip, oom-pah moment that speaks volumes.

The CSO performance is top notch throughout, with exceptional solos by the winds (a cast who bring vivid characterization to everything they play) and agile, focused playing by the strings (how they scamper in the Allegro).

The Direct Stream Digital recording by Telarc, the last for the CSO by Telarc, which ceased operations earlier this year, sounds full and rich in Music Hall’s warm, welcoming acoustic.