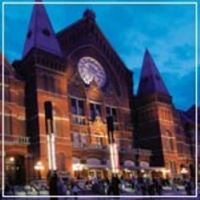

Mahler Makes Music Hall Sing

It was SRO (standing room only) at the Cincinnati May

Festival May 30 at Music Hall, final night of the annual event.

And not just for the extra brasses in Mahler’s Symphony No. 8, who performed from the top of the gallery.

Every ticket was sold, something which is not supposed to happen in the 3,516-seat hall, but does once in a great while.

Having every seat

full only added to the excitement of the evening, which saw music director

James Conlon joined onstage before the concert by Ohio Gov. Ted Strickland, who

presented him with a proclamation honoring his 30 years as May Festival music

director.

A torrential rainstorm slowed traffic on the way to the concert, but the sun came out just in time to get most people inside without being drenched.

Mahler’s gigantic opus is the kind of thing Music Hall was built for and it was gratifying, as well as great fun, to see it put to ideal use.

Assembled onstage

were the May Festival and Cleveland Orchestra Choruses (over 260 voices), the

Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra (augmented to 110 players), seven vocal

soloists and Conlon.

The 86-voice

Cincinnati Children’s Chorus occupied the right-most section of the balcony,

with the extra brasses one level up, making

close to 500 performers, quite a decent ensemble for Mahler’s so-called

“Symphony of a Thousand.”

The soloists, lined up behind the CSO in front of the chorus, were sopranos Bridgett Hooks and Ellie Dehn, altos Catherine Keen and Jill Grove, tenor Rodrick Dixon, bass-baritone James Johnson and bass James Creswell.

When the CSO basses and organist Heather MacPhail struck the opening E-flat Major chord, answered immediately by the chorus’ full-throated “Veni Creator Spiritus," the hall sang like a fine instrument in response.

Would that everything fit Music Hall so well, but for this evening, it was time to relax and enjoy the advantage.

Conlon, 59, cut an impressive figure on the podium, wielding his baton with emphatic downward strokes and utilizing gestures that swept up the formidable forces arrayed before him. Mahler was ever able to craft chamber music textures from huge resources, and Conlon was closely in touch with the smallest moments in the score.

The Latin text that constitutes part one of the symphony got a joyous reading. (“Veni Creator Spiritus” is a hymn to the Holy Spirit dating from the 10th century.) Balances were excellent, the voices blending with or rising above the orchestra as needed. The children’s voices emerged with touching clarity on their “Gloria’s,” which were echoed by soprano Bridgett Hooks and the CSO.

The soloists sang with fervor, the brasses soared and timpanist Patrick Schleker laid on his sticks to thrilling effect. What can nevertheless devolve into a shout fest (Mahler uses the voices like instruments here) showed considerable subtlety.

Part two is a setting of the final scene of Goethe’s “Faust.” This is Faust welcomed into heaven, his bargain with Satan defeated by redeeming love. Dedicated to his wife Alma, it is Mahler at his most optimistic. Like his Symphony No. 2 (“Resurrection”) it expresses a belief in eternal beneficence and reconciliation.

It takes a while to unfold (the movement is longer than most symphonies), but it does so with a powerful inevitability, like a force of nature asserting itself gradually -- even gently -- before its fullness is revealed.

The scene begins in the wilderness, a barren spot expressed musically by brushed cymbal (percussionist Bill Platt), string tremolo, softly treading bass pizzicato and plaintive woodwinds. When the chorus of anchorites enters, it does so in halting whispers, setting the stage for the drama to come.

Johnson as Pater Ecstaticus evoked love in a radiant voice. Creswell followed suit as Pater Profundus, who explicates the love inherent in nature itself.

As the angels who come bearing Faust’s soul, the women and children sang with affecting lightness (“Rejoice, it is fulfilled”). Dixon as Doctor Marianus, the mystic who addresses the Mater Gloriosa (Virgin Mary) when she appears in the sky, stumbled at one point. Although he caught himself quickly and soldiered on through the evening, his voice showed strain, probably from his work earlier in the festival.

Magna Peccatrix (Mary Magdalene), Mulier Samaritana (the Samaritan woman), Maria Aegyptica (a fourth-century saint) and Una Poenitentium (Gretchen, Faust’s earthly love) were sung with beauty and distinction by Hooks, Keen, Grove and Dehn, respectively. The CSO’s Paul Patterson put aside his violin for a mandolin as Dehn interceded for Faust in one of the symphony’s loveliest moments. Soprano Hana Park responded from the gallery as Mater Gloriosa, welcoming the penitent with “Komm! Hebe dich zu höhern Sphären" (“Come, raise yourself to higher spheres”). Joan Voorhees on piccolo joined with harps and celesta in an ethereal moment as the music lingered in anticipation.

To end the work, Mahler echoes his “Resurrection” Symphony with music of transcendent beauty and power. The Chorus entered whisper-soft on the final “chorus mysticus,” where Hooks floated an exquisite high C. The voices built to a triumphant affirmation of universal love, followed by a shattering, brassy repetition of the “Veni Creator Spiritus” theme by the CSO.

The ovation was long and loud, with repeated acclamation for Conlon in a demonstration of affection long to be remembered.

For the traditional singing of “Hallelujah” from “Messiah,” I had the best seat in the house, right next to baritone Thom Mariner, whose handsome voice sent the familiar lines soaring through the crowd.