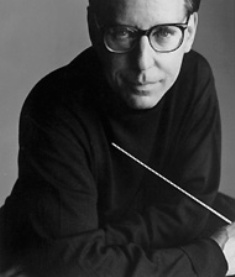

Dreams Can Come True: Gilbert Kaplan and Mahler

You just want to cheer for Gilbert Kaplan.

His story sounds like a fantasy right out of Walt Disney, but it's true:

At 24, Kaplan, a young economist working for the American Stock Exchange, heard Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 (“Resurrection) for the first time. Like a fairy tale prince, he fell in love with it immediately.

At age 40, a multi-millionaire having made his fortune as founder/editor-in-chief of Institutional Investor magazine, he decided to pursue his first love. He plunged into Mahler research, acquired the autograph copy of the "Resurrection" Symphony and began work on a new performing edition.

A lifelong music lover, but with only three years of piano study as a child, Kaplan decided to go even further and take the ultimate risk: conduct the symphony himself.

(Worse than failing would have been not doing it at all and wondering what would have happened if he had tried, he told Charlie Rose in a 1996 interview.)

Kaplan took conducting lessons, consulted with leading maestros, practiced tirelessly and committed the 80-minute score to memory. He hired the American Symphony Orchestra for a private performance at New York's Avery Fisher Hall in 1982. He expected it to be his last performance. Instead, the orchestra invited him back.

Since then, he has conducted the "Resurrection" Symphony with more than 50 orchestras, including the Vienna Philharmonic, made two recordings (one the best-selling Mahler recording ever) and even performed it on opening night at Austria's sacrosanct Salzburg Festival in 1996. In short, he has become a leading exponent of the work and an international Mahler expert.

Friday night at Music Hall, Kaplan led the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra and May Festival Chorus in the U.S. premiere of his new critical edition (with co-editor Renate Stark-Voit, now recognized as definitive by the International Gustav Mahler Society in Vienna).

The ultimate Gilbert Kaplan lesson? "You can always do more than you think you can," he told Rose (see the interview at http://www.charlierose.com/shows/1996/12/19/2/an-interview-with-gilbert-kaplan).

Ah, but is there muttering in the background? Envy? Incredulity? Automatic dismissal?

Of course. And Kaplan, 67, readily admits that he did not embrace Mahler's "Resurrection" Symphony to become a conductor, but because he loves the work. It is the only music he conducts, and he has no larger ambitions on the podium (he accepts no fees for his conducting).

As played out with the CSO at Music Hall Oct. 18, the performance -- which included Kaplan wearing his scholar hat in a multi-media pre-concert lecture about Mahler and the Symphony No. 2 -- was absorbing for three reasons: as an introduction to the new edition of the symphony, as a showpiece for Music Hall as a venue and last but not least, for some moments of truly inspired music-making.

Kaplan is not a professional conductor. Fluid technique, unquestioned authority and the mysterious element of communication are not yet his, but he clearly knows the score, and when he and the CSO players connected the results were powerful.

His tireless efforts to arrive at Mahler's final thoughts on the Symphony No. 2 denote an understanding of the composer's desire for perfection. Though a score was not available to me, my impressions were of enhanced transparency, the creation of more chamber music-like textures (featuring first-desk string solos at several points) and the overall goal of building through contrast and accretion, to the cataclysmic conclusion where the voices of heaven and earth join in a celebration of love and redemption for all.

One suspects that Kaplan might be at home in front of a chorus, for the May Festival Chorus and vocal soloists Christianne Stotijn, mezzo-soprano, and Janice Chandler-Etienne, soprano, performed splendidly for him. Stotijn, in particular, with her lightly veiled mezzo, sang to halo-like effect in the fourth movement, "Urlicht" ("Primal Light"), shading her words with stopped vibrato and keen expression. The chorus stole in softly on their first "Aufersteh'n" ("Arise"), creating an eerie effect of humanity newly awakened.

In his collaboration with the 114-piece CSO, Kaplan achieved some beautiful results -- as in the buildup to the recapitulation in the first movement (which to this listener sounded as if it involved some re-scoring per the new edition), the warm, charming pizzicato episode with harp and flute in the Austrian Ländler movement and above all, in the fifth movement finale which exploded following "Urlicht."

Music Hall itself became an instrument here, with extremely effective offstage brass and percussion originating outside the auditorium doors on the gallery level (two bands, 10 players total). Synchronization with Kaplan and the CSO onstage was pinpoint, thanks to the CSO's two new assistant conductors Ken Lam and Vince Lee and TV monitors.

The "Resurrection march was fittingly wild and raucous -- a nice contrast with principal trombonist Cristian Ganicenco's earnest, pleading solo on the "O Glaube" ("O Believe") motif. Following in ratcheted-up succession were the chorus and soloists' ethereal affirmation of freedom from death and the all-stops-pulled conclusion.

Dreams can come true.