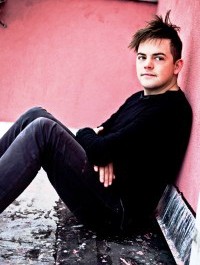

Nico Muhly Shines for Constella

Composer Nico Muhly tempts one to play with words:

He has been called “the hottest composer on the planet” (by the Daily Telegraph of London) and spends a lot of time in Iceland.

He performed his new work “The Planets” in March in Cincinnati and returned in October to star in the Constella (as in “constellation”) Festival of Music and Fine Arts.

Just 31, Muhly is exceedingly prolific. His published works number 122 (and counting), including two operas, one co-commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera in New York, to be performed during the 2013-2014 season.

As composer-in-residence for Constella, Muhly performed October 9 at Northern Kentucky University in Covington (across the Ohio River from Cincinnati). He led master classes at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music (CCM) and Cincinnati’s K-12 School for Creative and Performing Arts. CCM’s Café Momus Contemporary Music Ensemble performed a concert devoted to his music October 10. A whirlwind of energy, he nevertheless found time during his visit to share his thoughts on composing, performing, fame and his plans for the future.

People tend to have the wrong idea about composers, he said. “The model of the composer as receiving these inspirations is to me incredibly 19th-century. Take Bach, for example. He didn’t have time to be inspired. He had so much he had to write. He used to write every week -- you know, the choir is going to meet at this time and they’re waiting. It’s Sunday and you have to write a cantata, and it’s the fourth Sunday after whatever.” Under those circumstances, said Muhly, “the music is actually devoid of anxiety about what is it about?”

That’s the way it is with commissions, he said. “A commission is essentially a set of restrictions and they are very specific. It’s stuff like, ‘Write a piece for symphony orchestra between 15 and 18 minutes; this is the orchestra and we have a fabulous first oboe player.’ Basically what you get is a set of givens. You can ignore them if you want, but what it does is narrow the space in which you’re going to write. For me, that’s hugely productive, because you’re left with a really specific kind of précis. I feel it’s a spatial thing. It’s like someone said, ‘Design me a house.’ You’d be like, ‘What kind of house? Where is it?’ If someone took you to a site and said ‘Design me a house here,’ you could do it very easily.”

Born in Vermont, raised in Providence, Rhode Island, the son of a painter and a documentary film maker, Muhly absorbed a wide variety of music growing up. “I grew up in an environment where one listens to everything. There was nothing that was off the table. My parents were the sort of hyper-educated people who were a little too old to be hippies, but a little too young to be Beatniks. The record collection was wide and deep, everything from Takemitsu to Bonnie Raitt.”

He sang in an Episcopal Church choir where, again, the music was “for use” rather than the glory of the composer. “That kind of music-making was enormously influential for me,” he said. “Religious music is a large part of my practice. I’ve written a lot of music for the Anglican Church. There’s a disc of some of it out (“A Good Understanding”) and I’m writing a lot more this year.”

Muhly majored in English literature at Colombia University before attending the Juilliard School of Music under the Columbia-Juilliard joint degree program. “For me, it was about learning to think critically. It was about getting an actual education. I mean, going to Juilliard is essentially like going to trade school. At Columbia, you have to take classes outside of your major, in science and so on. And you meet people who have other interests, who end up in other places.”

He studied composition at Juilliard with Christopher Rouse and John Corigliano. And although he was never his student, he worked for composer Philip Glass as a MIDI programmer. “I met him through a friend of a friend. His publishing company needed someone who could do this, and I just sort of made myself useful for eight years. Philip is one of the most generous people, supportive without being meddlesome.”

All of these influences went into the mix for Muhly, who has composed for a wide variety of ensembles and artists, including the American Ballet Theater, New York Philharmonic, Opera Company of Philadelphia, violinist Hilary Hahn, soprano Jessica Rivera, percussionist Colin Currie and pianist Simone Dinnerstein, among others. He has performed, arranged and conducted for Antony and the Johnsons, Jónsi of the band Sigur Rós, Grizzly Bear and Usher, and has composed for films including “Joshua,” “Margaret” and “The Reader.”

“One of the difficulties about the way music was taught in the last century is that education taught you to discriminate against unnecessary musics, and you could sort of sift stuff outside of the canon. This, I think, was undone by people born in the 80s, as I was. There’s a sense of that having been a mistake. As with all these sort of revolutionary things, it went a little too far and it excluded too much, and a lot of the music ended up sounded rather robotic and dopey.”

Muhly’s concert at NKU took place in the school’s new, high-tech “Digitorium.” The visually enhanced, electro-acoustic program included the world premiere of a Constella commission, Three Songs for tenor and violin on surrealist love poems by Andre Breton and Jacques-Bernard Brunius. Soloists were tenor Grant Knox and violinist Tatiana Berman. Also on the program were three pieces for piano and electronics, with Muhly at the piano (see review at musicincincinnati.com/site/reviews_2012/Nico_Muhly_Meets_the_Digitorium.html)

The Café Momus Contemporary Ensemble performed five pieces by Muhly and the Concerto for Nine Instruments, Op. 24, by Webern in Patricia Corbett Theater at CCM. They included Muhly’s Three Songs (premiered October 9 at the Digitorium), “Step Team” (2007), “Motion” (2010), “Honest Music” (2003) for violin and tape and “By All Means” (2004). In “Honest Music,” violinist Erica Dicker performed against tape with apparent ease. This is a formidable task, said Muhly.

“One of the great paradoxes of working with prerecorded materials is that you think using recorded material gives you an element of control that you wouldn’t have performing with people. Actually, what performance nerves, adrenalin and all that does is that you second-guess yourself and end up feeling like the tape, the prerecorded elements, are changed in some weird way. ‘Skip Town’ (one of the three piano pieces her performed at NKU) is always the same, always me versus the tape, always in the same way. And yet every time I play it – literally every time – I feel like it’s different, just because your nerves are different.”

A resident of New York’s Chinatown, Muhly formed a connection with Iceland through singer/songwriter Björk. “She rang me up -- sort of this weird music world -- and I ended up putting down roots there. I met a wonderful community of musicians and non-musicians (the Bedroom Community, an artist-run record label/collective) and just realized very quickly that this was a place that really valued music on a simple, social level.” A frequent collaborator with members of Bedroom Community, Muhly is even studying Icelandic. “It is essentially the first Scandinavian language, almost unchanged from Old Norse. All other Scandinavian languages derived from it.”

Which brings one back to “hottest composer on the planet.”

“It’s irrelevant,” he said. “I mean, quite honestly, in classical music that stuff can be as damaging as it is kind. You just have to try to ignore it and keep on making good work, because it’s so irrelevant to the actual business of choosing the right notes and the right rhythms, which is all I’m being paid to do.”

Of plans for the future, Muhly has none, he said. “Despite the fact that I’ve written a lot, I’m very unambitious. There is no plan. In fact, there’s kind of the opposite of a plan. I want to do everything. I want to radiate out instead.”