Philip Glass' Symphony No. 5: From Chaos to Enlightenment

(first published in The

Cincinnati Post April 25, 2003)

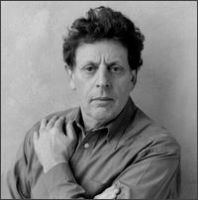

Composer Philip Glass, famed for his portraits of Einstein, Gandhi and Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaton, takes on the universe with his Symphony No. 5.

Written in celebration of the millennium and subtitled "Requiem, Bardo, Nirmanakaya," it’s100 minutes long with no intermission. There are 12 movements representing a cycle of creation from chaos to enlightenment.

The monumental work, premiered in 1999 at the Salzburg Festival in Austria, comes to the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music’s Corbett Auditorium at 8 p.m. April 26. It will be a regional premiere.

Performing will be the CCM Concert Orchestra, CCM Chamber Choir and Chorale, the Cincinnati Children’s Choir, soprano Kelli Domke, mezzo-soprano Lauren Pastorek, tenor Christopher O’Conner, baritone Marc Callahan and bass-baritone Dong-Geun Kim. CCM’s Earl Rivers will conduct. Glass will present a pre-concert lecture with CCM dean Douglas Lowry at 7 p.m.

Arguably the world’s most popular contemporary classical composer, Glass himself has been surprised by the work’s reception by the public.

"It’s a huge undertaking," he said by phone from New York. "I felt, we’ll do it in Salzburg and that would be it."

But it wasn’t just size that gave Glass doubts. The texts - drawn from the world’s great "wisdom" traditions, from the Rig Veda to the Mayan Popul Voh - are not light reading by any measure. "I thought, it’s just too esoteric. People aren’t going to be interested.

"Well, I was completely wrong. To my surprise, it’s been done every year, all over the world."

The appeal of Glass’ music is one reason. (There is an address on the web for "The Advanced Center for Treatment of Philip Glass Addiction.") Another is its dramatic impact (disliking the tag "minimalist," Glass calls his style "theater music"). As for the texts, Glass uses them in English translation.

English was chosen for two reasons, he said. "For one, I wanted as much as possible for it to be understood by the audience. If we did it in Japan, Belgium or Austria, it was much simpler for them to translate it from English back to their own language."

Presenting the texts in one language also "gave it astonishing coherence, one that we hadn’t anticipated. They almost sounded as if they were written by one person. It tends to underscore the strength and universality of the ideas and the messages."

The texts are from "every period and every continent" and include the Bhagavad Gita, the Bible, Koran, Hawaiian Kumulipo and Chinese, Tibetan, Japanese, Native American and African sources. "These are thoughts that people have been having as long as you can remember."

The 12 movements are: Before the Creation, Creation of the Cosmos, Creation of Sentient Beings, Creation of Human Beings, Love and Joy, Evil and Ignorance, Suffering, Compassion, Death, Judgment and Apocalypse, Paradise and Dedication of Merit. "Requiem" comprises the first nine movements, "Bardo" ("in between’) numbers 10 and 11 and "Nirmanakaya" ("rebirth, enlightenment") the final benediction by 8th century Buddhist saint Shantideva.

Glass selected the texts with the help of James Morton, former dean of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City, and Kusumita Pederson, chair of religious studies at St. Francis College in Brooklyn.

"Jim provided most of the more traditional western type spiritual texts and Kusumita was very good at the things that were non-western."

The three met about 20 times over the course of a year. "I had outlined the way I wanted the piece to go. We went through it heading by heading, and I said bring me texts on this topic, like death or love. Then we would go over them and I would pick out the ones I liked."

Glass’ choices were "totally personal," he said. "I wanted to insure that the sources were very broad and international, both geographically and historically. I stayed away from the standard texts that you might find in the Christian and Hebrew traditions."

For example, "the fall of the angel who became Satan I took from the Muslim text. I felt it was so powerful. I asked Jim (Morton) to put aside his own predilection for Christian literature and to take a broader look."

As a result, "the ones we ended up with from the New Testament (Matthew, First Corinthians) I thought were astonishingly beautiful."

Glass practices no particular religion himself, he said. "My father was a confirmed atheist and I thought he was a pretty good guy. There were some Jewish traditions in the family, but we didn’t do very much of that. I had been in India many times (Glass studied with Ravi Shankar during the 1970s) so I probably had more familiarity with the Hindu and Buddhist texts than with the Christian ones."