A powerhouse performance by the Miró Quartet. opened Chamber Music Cincinnati’s 2013-2014 season and the 2013 Constella Festival Tuesday night in Werner Recital Hall at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music.

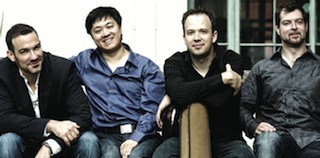

Joining first violinist Daniel Ching, violist John Largess and cellist Joshua Gindele was second violinist William Fedkenheuer, an addition to the quartet since 2011, when he succeeded former second violinist Sandy Yamamoto.

Quartet-in-residence

at the Butler School of Music at the University of Texas in Austin, the

much-honored ensemble brought their strength and perception to Beethoven’s

Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 130 -- including the awe-inspiring Grosse Fuge (Op. 133) -- and to open the concert, Schubert’s Quartettsatz in

C Minor and Quartet No. 14 in D Minor, “Death and the Maiden."

The Beethoven was, in all respects, the highlight of the evening. (Ching jokingly thanked Chamber Music Cincinnati for allowing them to program it.) A finer performance could not have been wished. Known for their virile, high-energy playing, the Miró foursome captured Beethoven’s late quartet in all its complexity and ambiguity. Opus 130 is a good-natured work, its six movements combining elements of the 18th-century divertimento with, in the Grosse Fuge finale, the most learned summation of contrapuntal writing (Beethoven was prevailed upon to provided a “simpler” alternative finale, but the trend today is to perform it as originally conceived).

The Miró’s mettle was evident from the outset as they negotiated the sudden metrical and dynamic contrasts in the first movement. Ensemble was tight even as they went from piano to sudden forte, often in the space of a single bar. The second movement – a perhaps tongue-in-cheek, two-minute Presto -- came off in delightfully squirrely fashion.

The players found subtlety in the Andante con moto, whose contrary indications (“poco scherzoso,” meaning "a little bit joking") only add to its charm. And they put a full measure of the latter in the “Alla danza tedesca” fourth movement, a German dance that had the musicians handing off bits of phrases at the end. The Cavatina fifth movement, a molto espressivo operatic aria sung by the first violin, was beautifully crafted. A movement that brought tears to Beethoven’s eyes as he wrote it (and even in recollection), it has an aching moment marked “beklemmt” (“oppressed”) where the violin whispers brokenly over the accompaniment. Ching gave this exquisite expression.

The Grosse Fugue, which begins with an Overtura setting out the elements of the fugue, was fully arresting in the Miró's hands, from the turmoil of part one, with its strident dotted rhythms, to the quiet and restraint which followed and the sections where Beethoven manipulates his material, including many starts and stops. The Miró found moments to sing as well as strive, and it was a thrilling workout throughout that brought their admiring audience to its feet in a spontaneous ovation. (What better encore but one of Beethoven’s scherzos, the jolly Scherzo Allegro from his Op. 18, No. 6.)

In many ways, the Schubertian half of the program seemed like a warm-up for the Beethoven (and an analogy can be drawn with Schubert’s admiration for the late Beethoven). “Death and the Maiden” has been interpreted as the composer’s essay on death, start to finish. It nevertheless seemed heavy-handed to this reviewer. The slow movement had many moments of beauty (Gindele’s cello variation touched the heart) but the Scherzo was a bit over-rough, and the finale, though Presto, with a prestissimo coda, strained the bounds of optimal articulation.