(first published in Express Cincinnati, June, 2010, www.expresscincinnati.com)

Moser, Nachtigal, Pogner, Sachs, Schwarz, Vogelgesang, Zorn

. . .

Meet the Meistersingers.

Cincinnati Opera artistic director Evans Mirageas did, at least in name, while waiting for his car to be serviced. Leafing through the local telephone directory, he found, not really to his surprise, the surnames of eight of the twelve master singers in Richard Wagner’s “Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg” (“The Mastersingers of Nuremberg”).

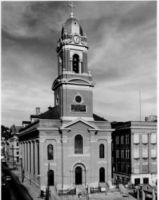

Considering Cincinnati’s German heritage, it could not be more fitting that “Die Meistersinger” will open Cincinnati Opera’s 90th anniversary season June 23 and 26 at Music Hall. John Keenan will conduct. Chris Alexander will direct, with bass-baritone James Johnson as Hans Sachs, soprano Twyla Robinson as Eva and tenor John Horton Murray as Walther. The musical roster has changed significantly since the opera was announced two seasons ago (see below), but the production is on track to honor Cincinnati Opera’s entry into its tenth decade.

Music Hall itself came into being in a manner not unlike Wagner’s opera.

As Mirageas pointed out in a workshop on “Die Meistersinger” May 8 at the Taft Center on Fountain Square, Wagner went to Nuremberg in the summer of 1861 and attended a pan-German choral festival. There were 240 choruses in all, totaling nearly 5,500 singers and an audience of 14,000. Wagner had drafted a story about the Meistersingers as early as 1845, but the 1861 festival gave him the impetus to complete the work. The premiere took place on June 21, 1868 in Munich.

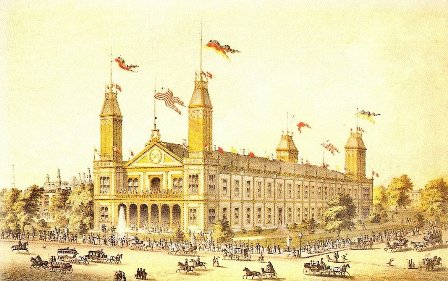

Similarly, it was a German choral festival that provided the catalyst for the Cincinnati May Festival. The 17th Sängerfest of the North American Sängerbund took place in Cincinnati in 1870 in a special Sängerfest Hall built for it at the corner of 14th and Elm Streets in Over-the-Rhine (site of the present Music Hall). Participating were 1,800 singers from 61 singing societies in the “Western” states.

Inspired by the event, Maria Longworth Nichols and her

husband George organized the May Festival.

The inaugural Festival was May 6-9, 1873 in Sängerfesthalle with a chorus

of nearly 800 representing local singing societies, regional choruses and a

108-piece orchestra organized and led by the country’s best known conductor,

Theodore Thomas. Over 6,000 people

attended the final concert. The event

focused attention on Cincinnati as a national cultural center. The music of Wagner was a major part of May

Festival repertoire from the beginning, with his Prelude to “Die Meistersinger”

heard on the very first Festival.

Sängerfesthalle, however, was a wood frame, tin-roofed fire trap not built for the ages, and when a thunderstorm nearly drowned out the next May Festival in 1875, Cincinnati grocer Reuben Springer stepped up with a $250,000 matching grant to build a new hall (a proposal unique for its time). Music Hall opened for the third May Festival in 1878 and has been its home ever since (having received municipal support to provide space for industrial expositions, it also served as Cincinnati’s virtual convention center for much of the next century).

Historically, Cincinnati is one of the most “German” cities

in the United States, with nearly half of its population of German

descent. Germans seeking political and

religious freedom, as well as a more prosperous life, came to Cincinnati in

droves during the 19th century, bringing their love of singing with

them.

Like their fellows from the British Isles, the Germans formed numerous singing societies. The North American Sängerbund was founded in Cincinnati in 1849 with five charter members, three from Cincinnati: Liedertafel, Gesang und Bildungsverein and Schweizer Verein (the others were from Louisville and Madison, Indiana). The group’s first Sängerfest took place in Cincinnati on June 1, 1849 in Armory Hall. It was a modest affair, with 118 singers and an audience of about 400.

Sängerfests grew exponentially, becoming biennial, then triennial after the Civil War. There were festivals in Cincinnati, Louisville, Columbus, Dayton, Canton, Cleveland, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Buffalo and Indianapolis. The Golden Jubilee of the North American Sängerbund took place in Cincinnati in 1899. It was a splashy affair, held in a brand new “Jubilee Sängerfest Hall” at the corner of Erkenbrecher and Vine Streets opposite the Cincinnati Zoo. The massed chorus numbered 3,000 singers from all over the country. There was even a competition for a prize cantata ($1,000, which went to Cincinnatian N.J. Elsenheimer for his allegory on the arts, “Valerian”).

The May Festival presented a special Sängerfest in honor of the Greater Cincinnati Bicentennial on May 1, 1988 at Music Hall. Guest choruses included the Combined Singers/Bakers Society, Dayton Liederkranz-Turner Chöre, Indianapolis Männerchor, Invitational Gospel Chorus, Cincinnati BoyChoir, Donauschwaben Singing Society, Musica Sacra, Southern Gateway Chorus and Sweet Adelines. Co-anchors were Edie Magnus and Jerry Springer.

A new, updated

“Meistersinger,” set in OTR in the 19th century, was the original

plan for Cincinnati Opera’s 90th anniversary, but it fell victim to

the recession last fall. Taking its place

is a period production obtained for a bargain price from Germany’s Düsseldorf Opera.

When the curtain goes up at 4 p.m. June 23

and 26 at Music Hall, it will be on the interior of St. Catherine’s Church in

16th-century Nuremberg, not Old St. Mary’s in Cincinnati circa

1860. The fit remains a good one,

however, and not only for demographic reasons.

The Düsseldorf production, by famed designer Günther

Schneider-Siemssen, may be set in 16th-century Nuremberg, but it is

not a huge stretch of the imagination to see parallels to 19th-century

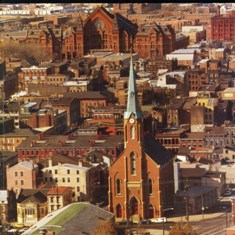

Over-the-Rhine. The neighborhood, bounded

on the west and south by the Miami-Erie

Canal (the “Rhine”) and by MacMillan and Reading Roads on the north and east,

was home to 90,000 people in 1895. Vine

Street, now Cincinnati’s East-West divide, was its bustling main street, lined

with tidy homes, shops of all kinds and cafes and beer gardens, where families

spent Sunday afternoons listening to local musicians and imbibing local

brew.

The Michael Brand Orchestra, which

in 1895 became the nucleus of the Cincinnati Symphony, performed in Weilert’s

Beer Garden on Vine Street.

Nuremberg in the 16th century boasted the most renowned of the German Meistersinger guilds. Objective of the guilds was to set lyric poetry to song according to strict, prescribed rules. Best known of the Nuremberg Meistersingers was Hans Sachs (1494-1575), a cobbler-poet who left over 6,000 works, 4,275 of them “meisterlieder” (master songs). Like Sachs, leading character in the opera, all of Wagner’s Meistersingers are based on historical figures.

The story has many facets. It is the love story of the young knight/would-be Meistersinger Walther von Stolzing and Eva, daughter of goldsmith/Meistersinger Veit Pogner. It is about Sachs, a widower who loves Eva, too, but denies himself to help the young lovers. It is about Wagner himself, mocking the critics of his day in the person of Sixtus Beckmesser, the buffoonish town clerk who also has his sights set on Eva. It is about art and the conflict between tradition and innovation. Who will get the girl? The winner of a song contest to be held by the Meistersingers the next day. The opera is famous for its choruses, soaring orchestral passages and Walther’s Prize Song.

Cincinnati native/Metropolitan Opera great James Levine, initially scheduled to conduct “Die Meistersinger” June 23 and 26, cancelled in April to undergo back surgery. His withdrawal was followed in almost domino fashion by seven of the leading singers: James Morris (Hans Sachs), Hei-Kyung Hong (Eva), Thomas Allen (Beckmesser), Evgeny Nikitin (Pogner), Kevin Glavin (Hans Foltz) and Richard Margison (Walther). All cited health reasons or personal or family matters.

John Keenan, Levine’s assistant at the Metropolitan Opera and a Wagner expert, was hired to replace Levine soon after his cancelation, and the resourceful Mirageas has assembled an essentially new cast headed by James Johnson as Sachs, Twyla Robinson as Eva and John Horton Murray as Walther. Hans-Joachim Ketelsen is stepping in as Beckmesser, Johann Tilli as Pogner and Kenneth Shaw as Foltz. All come highly recommended and help give the beleaguered event a kind of “Cinderella” aspect.

The Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra is the official orchestra for Cincinnati Opera.

For tickets and information, visit www.cincinnatiopera.org